One of the biggest fights at the United Nations climate summit in Glasgow is whether — and how — the world’s wealthiest nations, which are disproportionately responsible for global warming to date, should compensate poorer nations for the damages caused by rising temperatures.

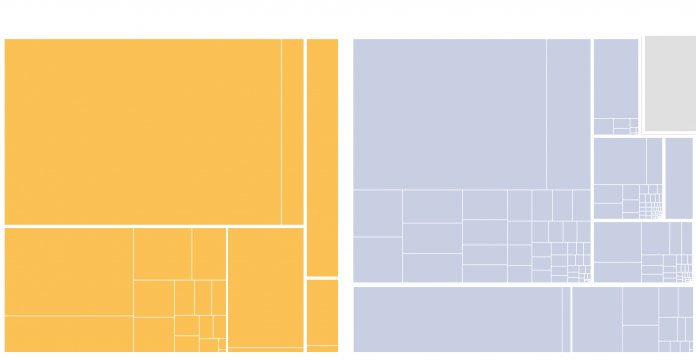

Rich countries, including the United States, Canada, Japan and much of western Europe, account for just 12 percent of the global population today but are responsible for 50 percent of all the planet-warming greenhouse gases released from fossil fuels and industry over the past 170 years.

Over that time, Earth has heated up by roughly 1.1 degrees Celsius (2 degrees Fahrenheit), fueling stronger and deadlier heat waves, floods, droughts and wildfires. Poorer, vulnerable countries have asked richer nations to provide more money to help adapt to these hazards.

At the summit, Sonam P. Wangdi, who chairs a bloc of 47 nations known as the Least Developed Countries, pointed out that his home country of Bhutan bears little responsibility for global warming, since the nation currently absorbs more carbon dioxide from its vast forests than is emitted from its cars and homes. Nonetheless, Bhutan faces severe risks from rising temperatures, with melting glaciers in the Himalayas already creating flash floods and mudslides that have devastated villages.

“We have contributed the least to this problem yet we suffer disproportionately,” Mr. Wangdi said. “There must be increasing support for adapting to impacts.”

A decade ago, the world’s wealthiest economies pledged to mobilize $100 billion per year in climate finance for poorer countries by 2020. But they are still falling short by tens of billions of dollars annually, and very little aid so far has gone toward measures to help poorer countries cope with the hazards of a hotter planet, such as sea walls or early warning systems for floods and droughts.

Separately, vulnerable countries have also emphasized that they won’t be able to adapt to every storm or every hurricane or famine worsened by climate change. The world will continue to warm. People will continue to die from climate related disasters. Villages will continue to disappear beneath rising seas. So, those countries, many of which still produce a tiny fraction of overall emissions, have asked for a separate fund, paid for by wealthy countries, to compensate them for the damages they can’t prevent. This issue is referred to as “loss and damage.”

“Lots of people are losing their lives, they are losing their future, and someone has to be responsible,” said A.K. Abdul Momen, the foreign minister of Bangladesh. He compared loss and damage to the way the United States government sued tobacco companies in the 1990s to recover billions of dollars in higher health care costs from the smoking epidemic.

Wealthy countries have historically resisted calls for a specific funding mechanism for loss and damage, fearing that it could open the door to a flood of liability claims. Only the government of Scotland has been willing to offer specific dollar amounts, pledging $2.7 million this week for victims of climate disasters.

At the same time, some of the world’s biggest developing economies are beginning to catch up on emissions. China, home to 18 percent of the world’s population, is responsible for nearly 14 percent of all the planet-warming greenhouse gases released from fossil fuels and industry since 1850. But today it is the world’s largest emitter by far, accounting for roughly 31 percent of humanity’s carbon dioxide from energy and industry this year.

China has endorsed vulnerable nations’ call for loss and damage financing at the climate summit in Glasgow, but so far China has not been pressured to contribute to such a fund. (So far, finance discussions at global climate talks have focused on the responsibility of developed countries, which the U.N. calls “Annex II” nations.)

Historical responsibility isn’t the only way to look at issues of justice and fairness. Another key metric is emissions per person. So, for instance, India as a whole produced about 7 percent of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions this year, roughly the same as the European Union and about half of the United States. But India has far more people than both regions combined, and is much poorer, with hundreds of millions of people lacking reliable access to electricity. As a result, its emissions per person are far lower today:

How these disputes over money get resolved is a major step in determining whether negotiators from nearly 200 countries can strike a new global deal in Glasgow to limit the risks of future global warming.