Speaking in early May, France’s President, Emmanuel Macron, called for a ceasefire between Russia and Ukraine and urged the West not to “give in to the temptation of humiliation, nor the spirit of revenge”.

The following day, Italy’s Prime Minister, Mario Draghi, speaking at the White House, said people in Europe wanted “to think about the possibility of bringing a ceasefire and starting again some credible negotiations”.

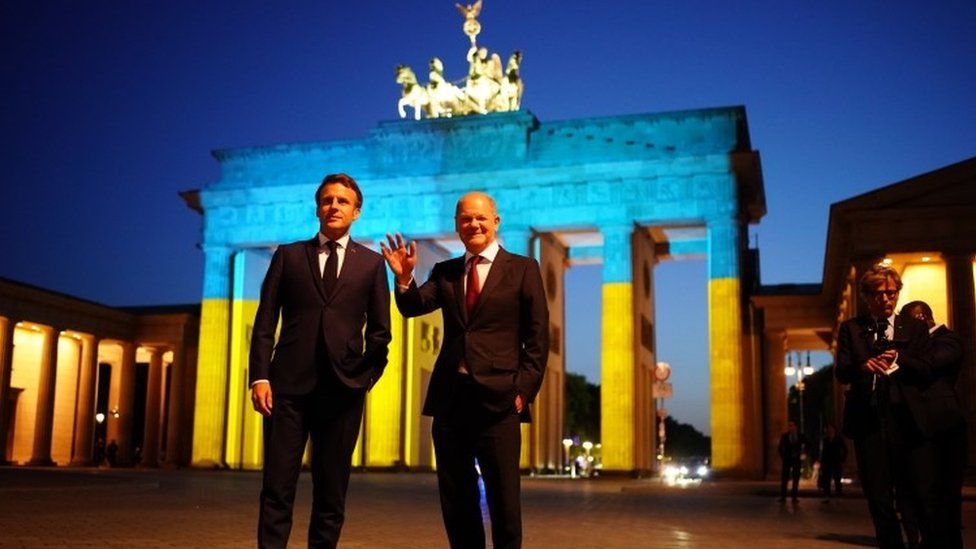

After Mr Macron and the German Chancellor Olaf Scholz held an 80-minute phone call with Mr Putin on Saturday, aimed at exploring ways to enable Ukraine to export grain through the Black Sea, Latvia’s deputy prime minister lashed out on social media.

“It seems that there are a number of so-called Western leaders who possess the explicit need for self-humiliation, in combination with a total detachment from political reality,” Artis Pabriks tweeted.

Mixed signals

Of course, it’s the US president who really matters to the Kremlin.

But Joe Biden has given different signals at different times. Calling Putin a “war criminal” back in March and seeming to hint at the need for regime change in Moscow, but also reluctant this week to send Ukraine rocket systems “that can strike into Russia”.

The former Prime Minister and President Dmitry Medvedev called that statement “rational.” But the US decision announced on Wednesday to send a more advanced rocket system to Ukraine was described by the Kremlin as “adding fuel to the fire”.

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESWith the US president prone to speak off the cuff, it generally falls to his Secretary of State, Anthony Blinken, to deliver the administration’s considered position.

At a recent Nato foreign ministers’ meeting in Berlin, Mr Blinken said the US and its partners were “focussed on giving Ukraine as strong a hand as possible on the battlefield, and at any negotiating table, so that it can repel Russian aggression and fully defend its independence and sovereignty”.

Strong words, but how exactly do you define “as strong a hand as possible”? And what does “fully” defending Ukraine’s independence and sovereignty actually mean?

So are cracks beginning to break up the veneer of Western consensus on Ukraine?

“You only have to look at the struggle to get the oil embargo,” says Ian Bond, director of foreign policy at the Centre for European Reform, referring to the tortured weeks of negotiation that resulted in this week’s partial EU embargo on Russian oil.

Any notion that the EU will move swiftly on to Russian gas has already been dispelled. The Baltic states and Poland would like this to happen quickly, but Estonia’s prime minister, Kaja Kallas, admitted this week that “all the next sanctions will be more difficult”.

Austria’s chancellor, Karl Nehammer, said a gas embargo “will not be an issue in the next sanctions package”.

More weapons needed

The West has promised much, Kyiv argues, but delivered less.

This week’s American and German promises to supply advanced multiple rocket artillery and air defence and radar systems will certainly have gone some way towards meeting the urgent demands of hard-pressed Ukrainian commanders.

But allegations of German foot-dragging over previous commitments and Joe Biden’s insistence that US weapons only be used to hit Russian targets inside Ukraine cause some to wonder why the West seeks to place limits on Ukraine’s war effort while Russia observes no limits at all.

“There’s a kind of calibration going on,” says Ian Bond. “As though we’re saying ‘we want the Ukrainians to win but not to win too much'”.

IMAGE SOURCE,REUTERS

IMAGE SOURCE,REUTERSIt’s widely believed that Mr Putin launched this war confident that the West would lack the stomach for a fight. That Nato members, fresh from their humiliating exit from Afghanistan, would shy away from a new international imbroglio.

Some recent reports from Moscow suggest a creeping confidence, engendered by gradual battlefield success and the belief, in the words of one source quoted by the Meduza website, that “sooner or later, Europe will tire of helping.”

The Kremlin may have taken heart from this week’s British government warning that as many as six million British households could face power cuts if Russia shuts off gas supplies this winter.

Could public anger in the West undermine support for Ukraine?

It’s a danger the US Director of National Intelligence, Avril Haines, spelled out to members of Congress last month.

“He [Putin] is probably counting on US and EU resolve to weaken,” she told members of the Senate Armed Services Committee, “as food shortages, inflation and energy prices get worse.”

IMAGE SOURCE,EPA

IMAGE SOURCE,EPAFor all the anxieties about self-inflicted wounds and the hesitation surrounding the supply of weapons, the Western consensus over Ukraine remains remarkably intact.

But the cracks that exist could still widen.

“If either side begins to make decisive gains, then they become more of a problem,” says Ian Bond.

“If the Russians completely break through Ukrainian lines in the east and start heading for the Dnieper River, the question of how much territory Ukraine should be willing to sacrifice to achieve a ceasefire is going to move up the agenda.”

By the same token, if Ukrainian forces start driving the Russians back, Ian Bond says, “there will be voices in the West saying ‘don’t try and recapture parts of the Donbas that the Russians have controlled since 2014’.”

It’s not a debate that seems terribly relevant just yet, but when the veteran US diplomat Henry Kissinger suggested at Davos that Ukraine should consider ceding territory in order to make peace with Russia, he met with a furious response in Ukraine and beyond.

A sign of anguished debates that still lie ahead.