Seventy-five years ago Sparsh Ahuja’s family was one of millions to flee their homes as British India split into two new nations, India and Pakistan. His grandfather never spoke of the place he fled as a young boy – until his grandson encouraged him to open up. It would lead to two families – separated by religion, a border and many decades – reconnecting once again.

Sparsh cradles three grey pebbles in his palm. They are precious to him – his only physical link to the land where his ancestors once lived.

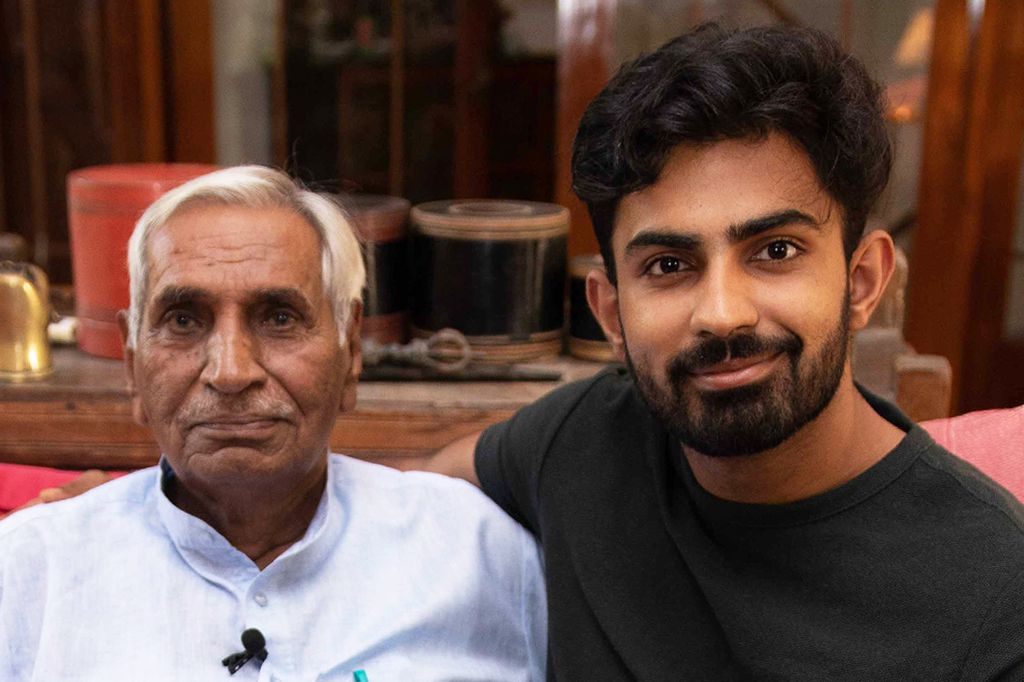

His journey to the stones began five years ago, when he was in India visiting his grandfather, Ishar Das Arora. Sparsh noticed the elderly man would jot down notes in Urdu. But Urdu was the official language of Pakistan. He knew his grandfather had originated from what became Pakistan, but little more. No-one in the family spoke of that time, says Sparsh.

“Even on the TV, or if we were playing a board game, and something about Pakistan came up, it was just a hush in the family.”

Sparsh was curious. One evening, over a game of chess, he began asking his grandfather about his childhood and that place no-one spoke of.

“He was really hesitant,” Sparsh recalls. “The first couple of times he was like, ‘This isn’t important. Why do you care?'”

But gradually, he opened up, happy that someone was showing an interest. Sparsh asked if he could record his family story – Ishar agreed. “He told my grandmother to find his best suit and tie. And he got all dressed up.”

Wearing a smart white shirt, his hair neatly combed, Ishar broke that “hush” about their family history.

Sparsh is in his mid-20s. He is thoughtful, chooses his words carefully, and has a gentleness about him. The conversation that day with his grandfather changed his life.

I meet him at his home in Brick Lane, east London. He explains how his grandfather had told him that he was born in Bela in 1940, a Muslim majority village, near Jand in Punjab. His grandfather’s parents ran a small shop on the side of the road selling peanuts. It was a peaceful time in undivided British India.

But, around the time of partition, when Ishar was seven, there were raids on the village.

- In 1947 British India was divided along religious lines – into Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority West Pakistan and East Pakistan (later Bangladesh)

- It sparked the largest migration in history outside war and famine – about 10-12 million people fled on both sides

- About a million people were killed in violence

Ishar and his family – who were Hindu – were taken to the house of the village chief, a Muslim man who gave them protection. When a mob brandishing pistols came knocking on the door looking for Hindus, the village head refused to allow them in. Ishar’s overriding memory was fear. He does not remember their subsequent migration to Delhi, where he still lives today.

Hearing this story in full – of a childhood in Pakistan, his Hindu grandfather being saved by a Muslim man, and the migration across a new border to India, changed something in Sparsh. He felt it was the first time he got to know his grandfather properly.

But it also set him on a mission. “I just knew straight away that I had to go back to that village. I just didn’t feel like our family story could be complete unless one of us went back and saw the place again.”

IMAGE SOURCE,SPARSH AHUJA

IMAGE SOURCE,SPARSH AHUJA

Sparsh then told his grandfather he wanted to go to Bela. Ishar responded: “No, it’s not safe. just stay here. What’s left there?”

But Sparsh wasn’t deterred. If anything, he was even more intrigued. Because while Ishar was palpably scared of his grandson returning, Sparsh noticed something curious – his grandfather still called Bela “home”.

Sparsh began making preparations to travel to Pakistan. “There’s a part of me there. Because I’ve grown up in so many different countries now – born in India, raised in Australia, and university and work in Britain, I don’t really feel like there is one place I can say, ‘This is where I am from.’ So I felt like there was just a missing piece of that puzzle I needed to see.”

In March 2021, Sparsh was in Islamabad, Pakistan’s capital. On the morning of the journey to his ancestral home, more than 100km (60 miles) away, he got up early. He wore a traditional blue salwar kameez and put on a white turban, wound in a special way. He had seen a picture of Ishar’s father – his great-grandfather – and wanted to go back to his village looking like him. He got into a taxi with two friends, and they set off. Sitting in the back seat, Sparsh was clutching a map given to him by his grandfather, sketched from old memories.

“My grandfather drew a mosque, a river and a hill they called the ‘echoing hill’. They used to go there and scream their name. And obviously the hill would echo back. That’s not very useful. You can’t put that on Google Maps,” Sparsh laughs, remembering. “And that was about it.”

- Inheritors of Partition can be heard on BBC Radio 4 on 8 and 9 August at 09:00 – and on BBC World Service on 9 August

- You can also listen on BBC Sounds

Sparsh was quiet on the long journey, lost in his thoughts. “What I was scared the most of was there being nothing there. I would have been really devastated.”

Gradually, the landscape grew more mountainous, the roads became uneven, the earth turned to red clay, just as Ishar had described. And then, out of the window, he saw people selling peanuts on the side of the road, just as his great-grandparents once did. He felt as though they must be close.

They arrived in a picturesque green valley, with a flowing river. There were fruit trees, cows roaming and mud huts. A sign read: Bela.

Sparsh got out of the car and, in his best Punjabi, spoke to an elderly lady, explaining why he was there. “She was like, ‘Oh, I don’t know anything about that. But the village head, he might be able to guide you.'”

As they drove into the village, more locals appeared. They were staring at Sparsh, “They were like, ‘Why is this random car showing up?’ And the thing is, it spread really quickly. The village was divided into three parts. By the time I arrived in the third part they already knew some random guy was driving around. People were just calling each other up.”

IMAGE SOURCE,SPARSH AHUJA

IMAGE SOURCE,SPARSH AHUJA

Sparsh found the village head. He introduced himself and explained that a man from Bela had saved his grandfather’s life nearly 75 years ago.

Did he know this man?

“He just goes real quiet. And he says, ‘You are talking about my father.'”

The village head was elderly, he had been a young boy at the time of partition. He told Sparsh he remembered his grandfather and his family. Overcome with emotion, Sparsh told him: “I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for your father.”

Sparsh was taken to the village head’s home to meet his son and grandson. They drank tea together. Sparsh heard a familiar story of how his family had been protected, but from another perspective told by the descendants of those who saved them.

Then they said they had something to show Sparsh.

The grandson and great-grandson of the man who saved Ishar took Sparsh’s hands and walked him through the village. They reached a courtyard. A building stood at its edge. Then the grandson said to Sparsh: “This was the mosque that your grandfather used to live next to.” He then pointed to a mud brick house and explained how that was the plot where Ishar had lived. Sparsh walked towards the centre of the courtyard and instinctively fell to his knees, putting his head and both palms to the dusty cracked earth. Eventually, when he stood up, the two grandsons – one Hindu, one Muslim – embraced.

Sparsh’s voice breaks as he remembers that moment. He says it was really emotional for him and that he had broken down in tears. “It was just the weight of that moment. I felt like I had finally made it there. It’s not something I ever expected would be possible in my lifetime, given the way these countries are.”

IMAGE SOURCE,SPARSH AHUJA

IMAGE SOURCE,SPARSH AHUJA

Before visiting Bela, he says he had felt angry about having lost something. But, once he saw his ancestral land, “a lot of that fire died down after that day.”

Sparsh says he was able to let go of “intergenerational trauma” a little bit.

“Because if you’ve grown up being told: ‘This is where we came from and we were never able to go back’ – that’s not the story I will tell my children. It will be: ‘We lost this land, but then we went back.’ It’s like that loop is now complete.”

Before he left the village, Sparsh took some grey pebbles from where his ancestors once lived, slipping them into his pocket.

That night, back in Islamabad, Sparsh WhatsApped his grandfather. Ishar responded: “I am proud of you. You have touched my motherland, which I could not explain in words.”

It took three generations for this traumatic story of partition to be re-written.

The two families are now connected on WhatsApp. They greet each other on their respective festivals, just as they used to when their ancestors were in the village together.

But there are no neat endings.

When things get tense politically, Sparsh says, his grandfather ceases contact on WhatsApp. “He says, ‘I don’t feel like messaging them now because I don’t know if it’s safe to.'”

And there are those on both sides with harder attitudes. Last year, Sparsh called out a social media post from one of the younger relatives of the village head in Bela, who said the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan had been a victory for Islam. Sparsh wrote to him saying: “You know, brother, by seeing your post, I felt really sad. It was to escape extremism like this that my nana [grandfather] had to flee the village in the first place.”

The village head’s family member in Pakistan apologised saying he didn’t mean to hurt anyone’s feelings. “It’s complicated,” Sparsh says. Further complicated, as some in Sparsh’s family hold anti-Muslim attitudes and support the ruling Hindu Nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

But there is a conversation at least.

IMAGE SOURCE,SPARSH AHUJA

IMAGE SOURCE,SPARSH AHUJA

The experience with his grandfather inspired Sparsh and some university friends to go a step further. They set up Project Dastaan – which uses Virtual Reality (VR) technology to help other families in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and the diaspora revisit places long since lost to history. Recently, Sparsh put a headset on Ishar and took his grandfather on a virtual tour or Bela – showing him the mosque near his old home, the land where his house once stood and the echoing hill.

Now, at the age of 82, Ishar is even thinking of going back to Bela in person. But as an Indian passport holder, it’s difficult to cross the border to Pakistan.

Sparsh gave one of the precious Bela pebbles to his grandfather, who keeps it beside his bedside table. The other two were used to make necklaces – one for Ishar, the other for Sparsh, who wears his remnant from another time every day.

IMAGE SOURCE,BBC/KAVITA PURI

IMAGE SOURCE,BBC/KAVITA PURI

Sparsh wants to hand his necklace down to his future children to keep a little bit of the village with them.

“As a South Asian, the whole idea of your soil, your homeland, is where you are from. It’s not something you can separate yourself from. Those pebbles are my ancestors. A bit of my past I can keep.

“I can’t look up my family’s histories and archives, so they will have to do for now. And that is why I want to make sure the future generation, at least in my family, has that.”