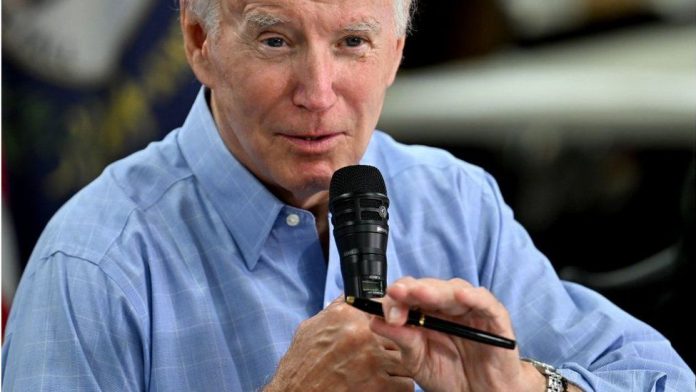

A day after the marathon voting session that saw his climate change bill passed by the Senate, President Joe Biden was off to Kentucky to meet people affected by flooding.

The state has been hit by a deluge that has toppled homes into rivers, left dozens dead and many more missing – the kind of event that will become more likely as a result of climate change.

For the president, it was a chance to cement his administration’s ownership of a landmark piece of legislation on one of the most important issues of our time.

And yet, despite a heartfelt speech aimed at those gathered around him whose lives had just been turned upside down, he never quite hit his mark.

Sure, he listed his achievements, including last year’s infrastructure bill and the help to reduce the cost of healthcare.

But he somehow glossed over his towering $370bn climate change action plan.

Channelling at times more quantity-surveyor than president, he spoke of digging trenches in which both water pipes and high-speed internet cables could be simultaneously laid.

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESThe gap between achievement and rhetoric was not lost on Ron Christie, a political strategist and former special assistant to President George W Bush.

“I thought to myself, what is he talking about?” Mr Christie told the BBC. “If you’re going to take a victory lap, at least have the presence of mind to talk more specifically and adroitly about what’s in this legislation, as opposed to just sort of mumbling through it.”

“And this is coming from a guy who has known and likes Joe Biden,” he added.

It’s a point that highlights the paradox of this presidency.

A man whose administration can point to significant legislative successes on some of the thorniest issues – infrastructure spending, gun control and now climate – doesn’t seem to be able to get the credit.

The polls show him to be one of most unpopular presidents in history at this point in the election cycle.

Months after he put his signature to that infrastructure bill – unlocking half a trillion dollars for new roads, bridges and broadband – only 24% of Americans surveyed knew that it had been passed into law.

Might this climate bill – with its $370bn dollars of incentives for electric cars and green energy production – also pass the electorate by?

“We simply don’t know how voters will respond to this bill yet,” says Casey Burgat, from the Graduate School of Political Management at George Washington University.

“Often it’s hard for everyday voters to immediately feel the tangible impact of bills, even with big, important pieces of legislation.

“Plus, we have months until the midterms, so the good feelings resulting from this win may completely wear off by then.”

Some of the headlines certainly suggest that Mr Biden may have now passed the low point of his presidency and could be on the brink of clawing back his approval ratings.

Despite being the oldest US president in history you can’t help but notice – in a political landscape long marked by paralysis and partisan deadlock – that he’s getting things done.

Miles Coleman, from the University of Virginia Center for Politics, thinks that the president is doing what he set out to do.

“After the chaos of the Trump administration, part of Biden’s pitch to voters during the 2020 election was that he’d be able to restore a sense of competency to government,” he said.

“If Biden goes ahead with his plan to run again in 2024, this bill will underscore his image as a president who’s been able to deliver on his priorities.”

The danger is, competency can be a bit, well, boring compared to what came before.

While some voters may well have craved a return to normality after Trump, normality doesn’t get noticed quite so much.

Compare, for example, the former president’s musings on climate change.

“They say the noise causes cancer,” Donald Trump said in a reference to wind farms during a 2019 speech, adding for good measure a loud whirring sound and moving his hand in a circular motion.

“And it’s like a graveyard for birds,” he went on.

It was hardly a policy. It had little basis in fact – at least the cancer part of it didn’t.

But compared to President Biden’s attempt to sell a complex and hard-won package of concrete measures that actually might go some way to limiting global temperature rises, it’s a far more memorable soundbite.

Democrats are undoubtedly buoyed by the climate result. It’s good for their base and it’s a demonstration of politics as the art of the possible.

But if that success is going to translate into a political dividend, those in Mr Biden’s party eyeing re-election battles in just a few months’ time will want to see signs of it soon.