Many foreign policy challenges facing the UK’s new prime minister will find the White House in lockstep. But there’s one issue much closer to home where they are a gulf apart.

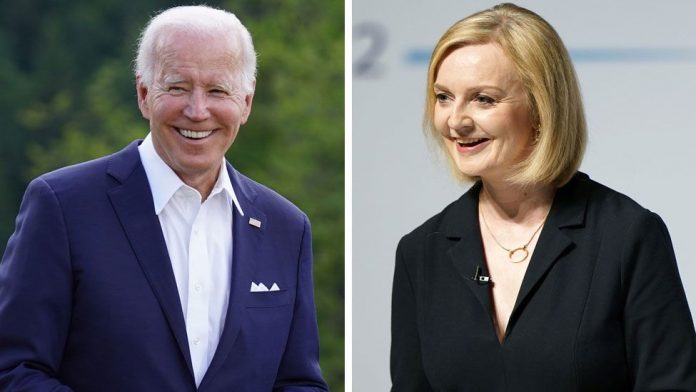

Ask most Americans – including most in Washington – what they think of Liz Truss and you will probably get a blank stare in return.

Indeed newspapers have been running headlines such as “meet the new UK prime minister” and, more bluntly, “who is Liz Truss?”

That could not be said of her predecessor, Boris Johnson, even before he became prime minister – a man once dismissed by Joe Biden as a “physical and emotional clone” of Donald Trump.

But the movers and shakers in Washington are now firmly focused on what Britain’s new leader will bring to the much-vaunted “special relationship” and whether she can resolve some key stumbling blocks that threaten to badly derail relations with the Biden administration.

The most serious and immediate of those is the impasse between Britain and the EU over the Northern Ireland Protocol which requires extra customs checks on goods moving from Great Britain to Northern Ireland.

As foreign secretary, Liz Truss has been at the forefront of UK government threats to unilaterally rewrite the protocol, something opposed by the EU and Washington.

“I do expect Liz Truss will be a lot more assertive on the matter,” says Nile Gardiner, director of the Margaret Thatcher Center for Freedom at the Washington-based conservative Heritage Foundation.

“I don’t think she’s going to be afraid of telling the US president directly in the Oval Office why America should be standing shoulder to shoulder with the UK on this.”

But it is an approach that’s likely to rile the current president and his party.

What is the Northern Ireland Protocol?

- Before Brexit, it was easy to transport goods across this border – both sides had same EU rules

- After Brexit, a new system was needed because the Irish Republic was in the EU but Northern Ireland was not

- Both sides (UK and EU) signed the Northern Ireland Protocol as part of the Brexit withdrawal agreement

- Instead of checking goods at the Irish border, the protocol agreed this would happen between Northern Ireland and Great Britain

- This allayed fears of a so-called hard border returning between north and south

- But Unionist parties are unhappy because they say it undermines Northern Ireland’s place in the UK

- Truss has proposed enacting legislation that could override the original plan

Joe Biden makes much of his Irish heritage and anything that threatens the Good Friday peace agreement is anathema to Democrats in Congress who believe the US was indispensable to ending political violence in Northern Ireland.

In their first call late on Tuesday, both Downing Street and the White House acknowledged that some discussion had taken place.

But Biden officials in their account of the call talked about not just “the importance of protecting the Belfast [Good Friday] Agreement”, but also the “importance of reaching a negotiated agreement with the European Union on the Northern Ireland Protocol”.

There was no such mention of talking to the EU in Downing Street’s version.

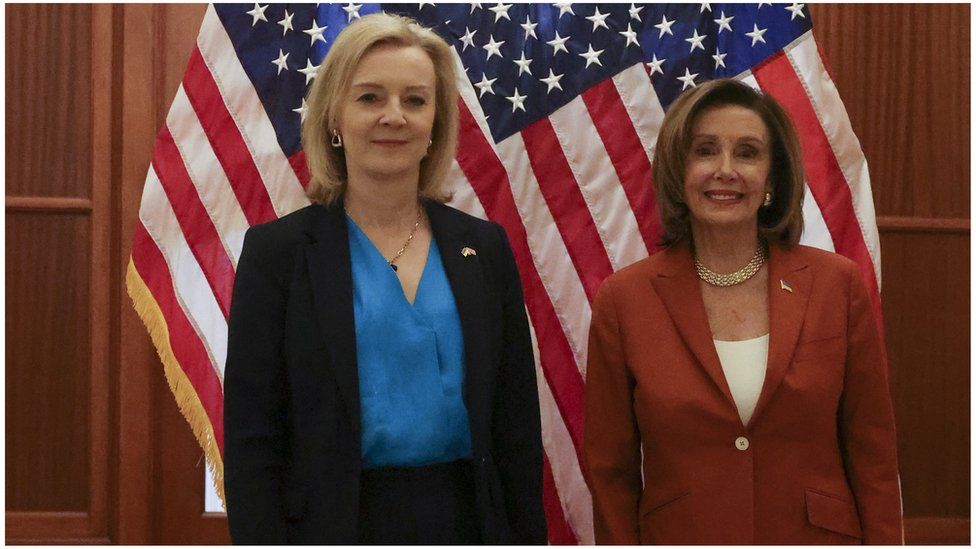

The significance of this issue to US Democrats is something Liz Truss will be well aware of as some of them made their views known, directly and forcefully, to her in the spring of this year when she travelled to Washington as foreign secretary.

IMAGE SOURCE,PA MEDIA

IMAGE SOURCE,PA MEDIAAmong them was Bill Keating, a Democratic congressman from Massachusetts who chairs the foreign affairs subcommittee on Europe.

He told the BBC: “It’s disappointing when a democracy engages in an international agreement that they were part of – and can be argued authored – and rescinds that, that’s difficult.”

Unhappily for London, its position on the Northern Ireland Protocol has become directly linked to the chances of an overarching trade deal between the UK and the US in the minds of many Democrats.

When Liz Truss was in Washington, both Bill Keating and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi told her that talks about a deal – a key objective of Brexit – would be a “non-starter” if the UK went ahead with unilateral changes.

“There’s no question, and it’s been clearly stated, that discussions on a bilateral trade agreement with the UK and the US would come to a halt because of this issue,” said congressman Keating.

It’s a point echoed by Frances Burwell, a distinguished fellow at the Atlantic Council. She predicts much “chillier” relations and fewer high-level visits between London and Washington if Britain pushes ahead with unilateral action.

“It has a great deal of potential to damage the relationship with this administration,” she said.

Who is Liz Truss?

- The former foreign secretary is 47, married, with two daughters

- She grew up in a left-wing family but gravitated to the Conservatives as a young adult

- She voted Remain in the EU referendum in 2016 but then embraced Leave after the vote

- Campaigned in the leadership contest as a tax-cutting, small-state Conservative

- Has unveiled a £150bn plan to tackle the cost of living crisis

In recognition, perhaps, of the lack of movement on a big deal, Ms Truss, particularly when trade secretary, championed a number of trade agreements with individual US states.

But no US state has the ability to affect tariffs and trade barriers, said Ms Burwell. “You cannot negotiate with Illinois and get a serious trade agreement.”

Prospects of a deal could improve after the midterm elections, should the Republicans take control of both chambers in Congress, according to Mr Gardiner.

“A lot of Republican politicians are very much in favour of getting a deal done and that includes Mitch McConnell who may well be Senate Majority Leader again.”

One Republican senator, Rob Portman, who has tried to advance legislation on a trade deal, echoed that enthusiasm, saying it would strengthen the relationship and improve the US’s economic competitiveness.

But if there is disagreement between Downing Street and the White House on the prospects on trade, there is widespread unity on a continuing close relationship on defence and intelligence.

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESThis was demonstrated by the recent UK US Australia deal on nuclear-powered submarines, known as AUKUS, and the continued emphasis on the so-called Five-Eyes – an intelligence relationship including Canada, New Zealand and Australia as well as London and Washington.

“These things are baked into the relationship,” said Frances Burwell. In these areas, she said, you don’t need the president and the prime minister to be entirely “simpatico”.

There will be differences in tone, she thinks, with Ms Truss sometimes “a little overly pushy in personal interactions”.

And while comparisons with Margaret Thatcher are inevitable, Nile Gardiner of the Heritage Foundation isn’t expecting a Reagan-Thatcher style relationship.

“The dynamics with Washington are going to be complicated in the next couple of years… because you have a US president who instinctively isn’t very pro-British.”

But two of President Biden’s biggest foreign policy challenges – Ukraine and China – could be key rallying points for London and Washington.

IMAGE SOURCE,UK GOVERNMENT

IMAGE SOURCE,UK GOVERNMENTMs Truss has a more hawkish approach to China than Boris Johnson, who once described himself as “fervently sinophile”. She will find herself more in line with President Biden who has taken a particularly tough line, as tensions are heightened over Taiwan.

And on Ukraine too, Britain’s robust approach is appreciated in the Biden administration although there are slight differences in emphasis.

Washington sees the war going on for years to come; and rapidly rowed back on some casual references to regime change in Russia by the president earlier this year. Liz Truss has talked about Vladimir Putin’s defeat.

But for the time being, strategy is closely aligned, particularly over maintaining the flow of lethal aid to Ukraine and measures such as the proposed oil price cap, aimed at preventing Russia from charging more than cost price for its oil.

Each new leader in London and Washington brings a new emphasis and definition to the so-called special relationship. Its intensity ebbs and flows; the parameters shift over time.

Cultural, historical and linguistic ties do count for something, though sentimentality, in the modern world, does not.