India has some of the most spectacular fossils on the planet, from vast beds of dinosaur eggs to strange prehistoric creatures new to science. But many are just sitting in the ground.

In 2000, while visiting the Central Museum of Nagpur in Western India, the paleontologist Jeffrey A Wilson found himself hunched over one of the most fascinating fossils he had ever set eyes on. One of his colleagues had excavated the specimen in 1984, in the village of Dholi Dungri in Gujarat, on the western coast of India.

“It was the first time that the bones of a baby dinosaur and its eggs were found together in the same specimen,” says Wilson, an associate professor of the Department of Geological Sciences at the University of Michigan, US. But to his amazement, there was something more. “In this specimen, the bones that I was examining had two little vertebrae with a special connection – something only snakes had,” he says.

To make sure he didn’t misinterpret it, Wilson looked for the same pattern along the spinal cord. And sure enough, he found it. “It was like a light bulb had gone off in my head. Could there be a pre-historic snake in this fossil as well?”

There wasn’t a facility in India that could do the deep cleaning the fossil required. It took Wilson four years to get approval from Geological Survey of India (GSI), a government-run body that oversees geological surveys across the country, to transport the specimen to the US. When the time came, he packed it all into a box, and put it in a backpack which he carried with him back to the United States, he says. Once there, it took an entire year of cleaning to remove the rocky matrix around its soft and delicate bones.

In the years that followed, scientists, paleontologists and snake experts pored over the fossil.

In 2013, with Indian paleontologist Dhananjay Mohabey and others from GSI, Wilson co-authored a paper describing the incredibly action-packed moment that the fossil captured. They not only confirmed the presence of a prehistoric snake, but also found that its jaws were opened wide as if to eat the baby dinosaur – one that had just hatched. The hatchling was beside a clutch of dinosaur eggs, which were still whole. The geologist studying the project deduced that the animals had probably been buried in a mudslide – an event that began quickly, without warning, locking away that predatory moment in time.

And that’s how Sanajeh indicus made its global debut – the words are Sanskrit for “ancient gape from the Indus”. Scientists noted how pre-historic snakes didn’t have the ability to open their jaws wide enough to swallow big prey, an ability that some modern snakes have acquired through the process of evolution.

In 2013, a similar specimen was discovered in the same spot and the team is now preparing another paper that describes how the anatomy of Sanajeh indicus closely resembles that of modern lizards.

In this way, fossils can unravel secrets of an ancient past that we wouldn’t be privy to otherwise, but despite the groundbreaking findings that have informed science in recent years, there just isn’t enough funding or systematic study of India’s immense fossil wealth, paleontologists say.

“I think India’s fossil heritage is largely untapped and has been forgotten,” says Advait M Jukar, a research associate in the Department of Paleobiology at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC. “India has produced the earliest whales, some of the largest rhinos and elephants that have ever existed, vast beds of dinosaur eggs, and strange horned reptiles from before the age of dinosaurs. But there are so many gaps that still need to be filled.”

And that’s because large parts of India have not been systematically explored by professional paleontologists.

Evolutionary puzzles

In spite of this, over the years, major paleontological finds from India have helped scientists piece together critical information to debunk old theories and shed new light on how life has evolved over time.

At the heart of many of these discoveries is Ashok Sahni, a pioneering paleontologist whose grandfather, father and uncle were all in the field. Sahni often uses his own funds to power his expeditions – his personal collection of fossils has filled the shelves of Punjab University’s Natural History Museum.

In 1982, at a dinosaur site in the blazing heat of the central Indian city of Jabalpur, Sahni remembers covering every inch of ground in search of fossils. When he bent over to tie his shoelaces, right there in front of him were four or five spherical structures, measuring 16-20cm in length. “These were very weathered, round, roughly of equal shape. I was stunned. Could they be dinosaur eggs?”

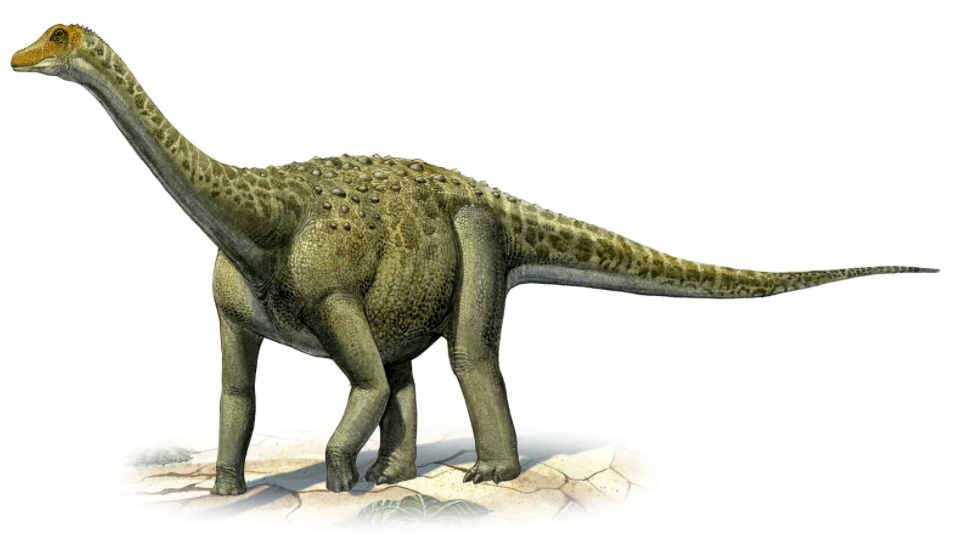

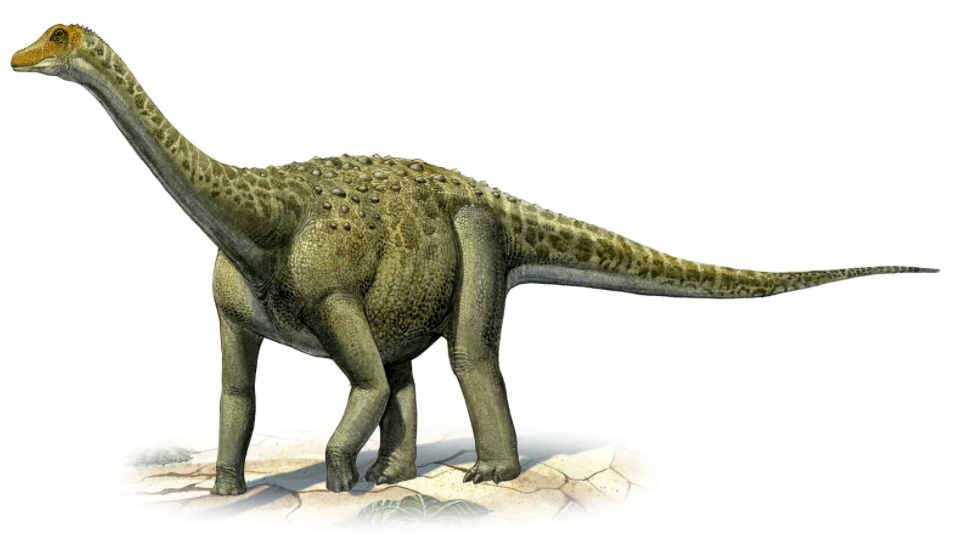

Indeed, they were the eggs of the Titanosaurus indicus, a large herbivorous dinosaur from the Cretaceous Period. It was the first time a clutch of dinosaur eggs had been discovered in India. Today, nearly 40 years later, nesting sites of dinosaurs have been found all over the country.

In August 2003, Sahni shot to global fame after 20 years of excavating, identifying and piecing together the bones of India’s newest species of carnivorous dinosaur, Rajasaurus narmadensis, which is thought to have been 30ft (9.14m) long.

But it’s Sahni’s less glamorous, lesser-known discoveries that have really informed science.

In 2010, he was part of a team of Indian, German and US scientists who discovered perfectly preserved insects in amber, estimated to be more than 54 million years old. The discovery came from a lignite mine 30km (18.6 miles) northeast of Surat in Gujarat, and it indicated that today the region could be home to some of the oldest deciduous forests in the world. “The published findings challenged the notion that India was ever an isolated continent,” Sahni says.

Another important evolutionary event is that of whales from land-dwelling deer-like mammals. And research has revealed that all of the world’s whales originated in the sea beds of India and Pakistan. “We know what these early whales look like from finds in Kutch, and northern parts of India and Pakistan, but we don’t know much about what their precursors were like,” says Jukar.

But studying these pieces of the past also help us make sense of how we regard the future and helps us gauge the level of environmental damage we’re doing, he says. “For instance, most paleontologists agree that our species had a dominant role to play in the extinction of large mammals like mammoths around the world [during the last Ice Age]. We can then get a sense for how many ecological functions, like seed dispersal, or nutrient transport, may have been lost with those extinctions,” says Jukar.

Young fossil records can also help us gain an understanding of where living species used to live before humans transformed the landscape, and we can incorporate that information into future conservation or land management plans, he says. “We know that climate change causes species to move to their preferred environments. We can use information about where animals and plants lived in the past to better forecast where they might go in scenarios of future climate change,” he says.

“In the early 1900s British geologists were in India collecting more exhaustively, so today, if you want to see complete collections from Indian dinosaurs, you’ll need to go to London or New York,” says Wilson.

All this has had an impact, especially on a generation of Indian children who grew up knowing very little of their own indigenous dinosaurs. This struck Wilson when he first started working in India. He spotted models of the Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops greeting the visitors outside of Indian museums. “I would always wonder what the heck that was doing there? Instead, you should have a Rajasaurus, a Jainosaurus, a Rahiolisaurus. Indian children should know about Indian dinosaurs,” he says.

Building awareness is hard when this information does not find a place in school curriculums or textbooks. However, filling this void in recent years are individuals from all walks of life – particularly teachers, podcasters and children’s books authors.

Vaishali Shroff’s The Adventures of Padma and a Blue Dinosaur published in 2018 was designed to captivate kids. Using fiction and fantasy to weave in real details on Indian dinosaurs, it won the Best in Indian Children’s Writing award in the environment category in 2019.

Since then, Shroff has spoken to hundreds of school children in many Indian cities, acquainting them with various species of Indian dinosaurs and the major discoveries over the years. “I wanted children to fall in love with our country’s dinosaur fossil heritage and to make them aware of the fact that dinosaur fossils could very well be in their backyards,” she says.

Desi Stones and Bones is an independent audio story initiative on India’s rich dinosaur heritage, powered by Chennai-based journalist Anupama Chandrasekaran. Over a series of eight podcasts since 2013, she’s traced the journey of India’s fossil heritage, interviewing local people and the paleontologists who are seeking to protect it. “While India’s dinosaur heritage does largely languish in neglect, over the years, I’ve been fascinated by how passionate some locals are about protecting it,” Chandrasekaran says.

In 2018, she recalls a meeting with high school physics teacher Vishal Verma at his home in Manavar, a town in Central India, that made a deep impression on her. Verma’s home was full to the brim with cartons of fossils. He taught her to identify the pores on the shell of a fossilised dinosaur egg that can tell you whether it was a herbivore or a carnivore. She marvelled at how much of India’s knowledge of indigenous dinosaurs was self-motivated and often undocumented.

Lingering challenges

Even as awareness builds, in recent years, theft and vandalism of prominent dinosaur sites across the country have proven to be a challenge.

It’s not a problem unique to India though, points out Wilson. “In America too, if you find a fossil on your land, you can do with it what you want. There’s no law that protects dinosaur fossils – they’re treated like minerals. And there are plenty of challenges to that approach.” Unlike minerals, however, the value of a dinosaur fossil isn’t immediately apparent. In India, vast amounts of paleontological data is lost to mining and other development activities, says Wilson.

For many Indian paleontologists, the struggle is often far more basic – such as the lack of space to house bones. Without proper museum infrastructure, most fossils end up in the dusty corridors of university buildings, says Sahni. “The Rajasaurus finding was like that too,” he says. The bones were lying around for 20 years before they were identified and pieced together.

Erratic funding can hamper projects too. “If there are two projects that require funding – one on ground water and the other on paleontology, you can guess which one has more meaning in a developing country,” says Sahni.

There’s a pretty good correlation between a country’s GDP and fossil discoveries, and that’s largely because a field like paleontology requires a lot of funding, patronage, and world-class museums with fossil preparation labs and storage facilities, which developing countries often do not have, says Jukar.

Another, more pressing issue that hinders the study of Indian fossils is the need for greater regional cooperation between scientists. Indian paleontology just can’t exist in isolation, says Wilson, because India is inextricable from Pakistan, Myanmar and Bangladesh in terms of its fossil wealth. All these countries are one geological unit, but politics can make it difficult for scientists to travel and exchange information freely.” “But being able to do so is a really important step to further learning,” he says.