When Magnus Carlsen and Hans Niemann sat down to play each other earlier this month in the third round of chess’s Sinquefield Cup, few could have predicted the chaos that would unfold.

Niemann, a 19-year-old American and the lowest-ranked player in the tournament, was facing a man who had dominated chess for more than a decade.

Carlsen, 31 and from Norway, was undefeated in 53 games in classical chess, and had the advantage of playing white – thereby moving first.

But if Niemann appeared daunted, he didn’t show it. After confidently nullifying the advantage of the first move, he gradually took over the game. Facing a difficult defence in the endgame, Carlsen faltered and soon resigned in a hopeless position.

The result was shocking – but nothing compared to what was to follow.

Soon after the game, Carlsen withdrew from the tournament without explanation, despite there being another six rounds left – a virtually unprecedented move at the top level of chess.

As commentators, players and fans tried to understand why he had quit, Carlsen posted a tweet that included a video of football manager Jose Mourinho saying: “If I speak I am in big trouble.”

The message was widely seen as raising suspicions of cheating. No evidence was provided, nor had Niemann been named, but the inference seemed clear.

Then on 8 September, Chess.com, the game’s biggest online platform, confirmed it had removed Niemann for cheating on the site.

As allegations swirled, Niemann admitted to cheating online on two separate occasions aged 12 and 16 by using computer assistance, but denied ever cheating over the board – widely regarded as a much more serious offence – saying he was even prepared to play naked to prove his innocence.

He went on to accuse Carlsen, Chess.com and the world’s most followed chess streamer, Hikaru Nakamura, of trying to ruin his career.

“If they want me to strip fully naked, I will do it,” said Niemann.

“I don’t care, because I know I am clean. You want me to play in a closed box with zero electronic transmission, I don’t care. I’m here to win and that is my goal regardless.”

The idea of cheating in chess is not new – but the invention of the smartphone has made it much easier.

The best chess apps, many of them available for free, are now significantly stronger than even the top players.

By inputting games into an app, the computer will quickly show near-perfect moves. For that reason the use of phones in over-the-board games is banned.

But there have been cases of players finding clandestine ways to cheat, including one who was caught with phones strapped to his leg and a micro earpiece telling him moves.

Grandmaster Susan Polgar, one of the strongest women players ever, told the BBC the issue of cheating in chess had been a “serious problem” for many years, including at scholastic level, where parents and coaches have sometimes been banned from watching.

“Even when I do some simuls (playing against multiple opponents in one go) once in a while – an unimportant, unrated event – I’ve seen a friend stood there with a phone and the position, and then as I move away they discuss what the engine suggests.”

While cheating is much less likely at the highest levels of the game – in part because of much more stringent anti-cheating measures – she notes that it’s still possible.

“At the GM (grandmaster) level, they don’t need a computer to tell them every single move… there are a few critical moments in the game.”

Still, it’s highly unusual for a top player like Niemann to be accused of cheating.

Not since 2006’s “Toiletgate” has elite chess faced a comparable scandal. Back then, world championship challenger Veselin Topalov’s team accused the champion Vladimir Kramnik of cheating during his “strange, if not suspicious” trips to the bathroom.

A statistical analysis by Prof Kenneth Regan, widely regarded as the world’s leading expert on cheating in chess, found no evidence Kramnik had cheated.

At other times allegations have bordered on the absurd.

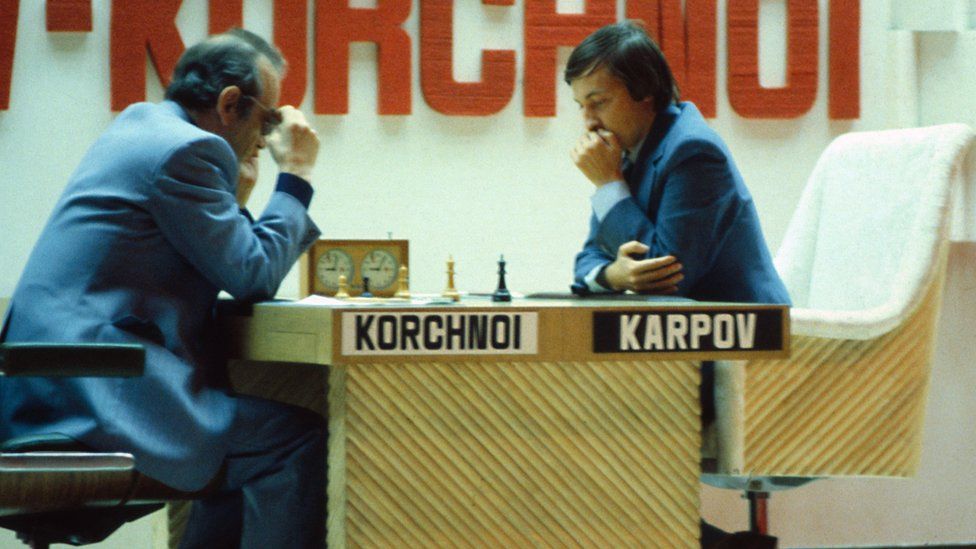

In 1978, world championship challenger Viktor Korchnoi’s entourage accused champion Anatoly Karpov’s team of cheating by sending their player a blueberry yoghurt. Team Korchnoi argued it could have been a signal to make a particular move.

The match was notable for the hostility and paranoia between both sides. Karpov’s team included a hypnotist seated in the front rows staring at Korchnoi, who in turn wore mirrored sunglasses, apparently to protect himself.

In the absence of any concrete allegations from Carlsen, the chess world has pored over games and interviews of Niemann for evidence of any cheating over the board.

Some have pointed to Niemann’s meteoric rise over the last 20 months, during which he surged from the relative obscurity of being ranked roughly 800 in the world to inside the top 50.

Nakamura has described the rise as “unprecedented”, though others have argued that Niemann’s progress, while fast, is comparable to other top junior players.

Still, for many in the chess world there is sympathy for the teenage Niemann – whose reputation has been tarnished despite no evidence of cheating in over-the-board games being presented.

Prof Regan, who is also an international master, analysed Niemann’s games and found no evidence of cheating.

Grandmaster Nigel Short, the only British player to compete in the final of the world championships, is also sceptical, saying there was no evidence Niemann cheated in his victory over Carlsen.

He told the BBC: “I think in the absence of any evidence, statement or anything, then this is a very unfortunate way to go about things. It’s death by innuendo.”

Short said another reason cheating at the top levels of chess was rare was that a proven allegation could end a player’s career. Cheating was more typical among players who were struggling to make a living competing in lesser tournaments with smaller prizes, he said.

For Short, Carlsen’s actions may be a reflection of the pressure he has been under as the world’s best player.

The Norwegian has been world champion since 2013 and has topped the world rankings for even longer. Earlier this year, he shocked the chess world when he said he would not defend his world championship crown again, citing a lack of motivation.

The move was all the more surprising because at 31, Carlsen is still in his prime and could have been expected to defend the championship many times more.

“It’s not a decision that most people would make,” Short said. “You normally go on, you fight, you take the money, eventually somebody is going to beat you.”

He added: “My feeling is that there’s some sort of inner turmoil with Magnus, maybe I’m wrong, but that is my impression looking from the outside… maybe it is altering his judgement.”

But while Susan Polgar said she wouldn’t speculate on the claims against Niemann, she said it was out of character for Carlsen to throw around accusations.

“He is not the kind of guy who will do some random thing. I’m sure he was aware before he said what he said and did what he did that this will stir a big commotion in the chess world.”

The saga took another turn on Monday, when the pair were re-matched in a major online tournament, which have become more common since the Covid pandemic.

Any thoughts that the issue of cheating might be put to bed were quickly dashed when Carlsen resigned after making only one move – an apparent protest at Niemann’s participation.

Despite taking the loss, Carlsen easily topped the qualifying group and revealed in an interview that he plans to issue a fuller statement on the scandal after the tournament ends. Niemann was knocked out in the quarter-finals.

For Polgar, the scandal is an unwelcome form of attention, detracting from the spirit of competition. Short, meanwhile, said Carlsen’s actions have arguably brought the game into disrepute.

But he sees an upside in the affair, which has been picked up by the world’s media, including US presenters Trevor Noah and Stephen Colbert.

“So the old adage that there’s no such thing as bad publicity,” he said. “Well, I don’t subscribe to it 100% – but there is always something in that.”