Technology has always dictated the way pop music sounds.

Hit songs are short and direct simply because, in the early days of vinyl and shellac discs, the music could last no longer than the time it took the needle to cross the gap between the edge of the record and the label in the middle.

The advent of magnetic tape allowed bands to record individual instruments and layer them up, prompting the fantastical sound collages of the Beatles and the Beach Boys. CDs meant that artists could break the 44-minute vinyl time limit – for better and, more often, for worse.

Spotify and TikTok have had their own impact on the way music is written and recorded. Research shows that 25% of listeners will reach for the skip button in the first five seconds. That’s why so many songs now begin with the hook or chorus.

Streaming has also exerted a downward pressure on song lengths (again, to avoid the dreaded skip button). Ten years ago, the average length of a UK number one single was 3’42”. Today, it is 3’16”, with songs like Lil Nas X’s Old Town Road and Nathan Sykes’ Wellerman clocking in at under two minutes.

And there’s even a streaming sound: A homogenous, mid-tempo cross between pop and rap that prioritises vibes over songwriting staples like crescendo, counterpoint and dynamics.

New York Times critic Jon Caramanica disparagingly calls it “Spotifycore” – but, done right, it boosts your chances of appealing to Spotify’s all-powerful algorithm.

Swedish pop star Tove Styrke, however, is fed up of it.

“I’m so sick of everything being the exact same formula,” she says.

“Everything is 2’30”. Everything has a really short intro that grabs your attention. Every vocal is so smooth that it doesn’t bother you at all.

“I wanted to do something different. It’s okay for a song to be 3’30”. Maybe you want to stay in that place a little longer. Maybe I want to have a guitar solo at the end.

“Everything doesn’t have to be so effective and condensed and perfectly manipulated just to fit a preconceived standard.”

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESThe proof comes on her new album, Hard – and more specifically on its almost-title track Hardcore.

What starts out as a cookie-cutter love ballad is suddenly and brutally interrupted by Styrke, unable to contain her emotions, shout-singing: “Go, make my heart explode / I want you hardcore“.

Music magazine Northern Transmissions called it “an insanely believable vocal“; while the Line Of Best Fit noted it was a “far cry from the perfectly-manicured performances” she gave as a contestant on Swedish Idol 13 years ago, “and all the better for it“.

“After we recorded it, I could barely speak,” reveals Styrke.

“I’m still struggling to play it live, because I can’t sing anything else afterwards.”

Like much of the album, Hardcore was written about her girlfriend… but perhaps not in the way you’d expect.

When they first got together in 2019, Styrke penned her a love letter in the form of Show Me Love, a doe-eyed riff on the 60s girl group sound. Subsequent lyrics, however, were a little more complicated. (Both videos show sexually explicit content).

“All of a sudden I started writing break-up songs, because I felt so vulnerable and scared of what would happen if this relationship ends,” she says, explaining the stakes were higher because the couple had been best friends before they fell for each other.

“I was horrified going into that relationship, so I wrote break-up songs to process that fear. Like, ‘Oh my God, how would I even handle something like that?'”

And how did her girlfriend react to those songs?

“I don’t know what she thinks is going on!” laughs Styrke. “But she’s heard me do phone interviews about the album back at home – so I guess she’s starting to understand the whole thing!”

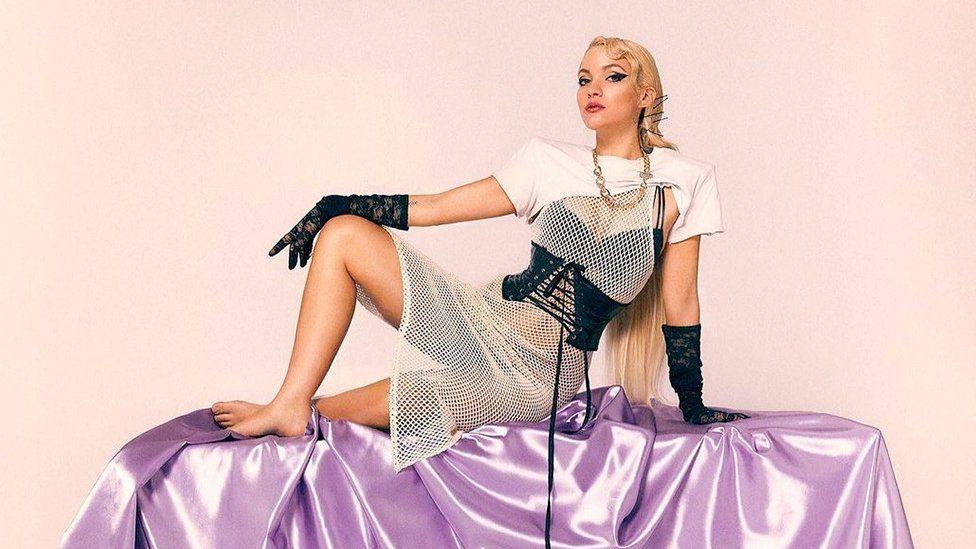

IMAGE SOURCE,SONY MUSIC

IMAGE SOURCE,SONY MUSICLetting her vulnerabilities show is a new thing for the Swede, whose previous songs include the sneering Even If I’m Loud It Doesn’t Mean I’m Talking To You and the imperious demands of Say My Name (Rolling Stone magazine’s song of the summer for 2018).

This time around, she opens up about her shortcomings, whether she’s falling prey to inertia on Millennial Blues, or admitting her tendency for self-sabotage on Bruises.

“I’m in a really healthy, wonderful relationship right now,” she says, “but I still identify with being that screw-up who can never be in a normal situation because you don’t think you deserve love.”

Letting go of that feeling was the first step towards fixing it; and it was paralleled by a similar, musical liberation.

Styrke’s previous album, Sway, was a tight, powerful pop record that was championed by Lorde and Katy Perry – but the process of making it left her drained.

“There’s not a single little sound or word on Sway that I didn’t go over a thousand times. I was so meticulous about everything.

“So this time, I wanted to go in a different direction and let go of that need to always be in control. Because what I’ve realised is, with the music that I enjoy listening to myself, it’s rarely edited and polished to the point where it shines.

“It’s the stuff that’s flawed, where you can feel a really strong presence of the person who made it.”

That’s why she’s not afraid to make a song like Hardcore “feel almost drunk”, with the beat staggering around her love-intoxicated lyric.

“That’s a very good example of something where I chose to not edit myself – because that lyric barely makes sense, but it feels right.

“I really tried to be a little bit more free this time and let the songs guide me.”

IMAGE SOURCE,TV4

IMAGE SOURCE,TV4Shrugging off the streaming formula has allowed Styrke to create a more human, more emotional version of her forward-thinking pop sound.

But she won’t be joining the likes of Halsey, FKA Twigs and Charli XCX, who’ve recently complained about record label pressure to go viral on TikTok – and she’s got a pretty good reason for that.

During the pandemic, the singer’s 2014 single Borderline suddenly started trending on the app, opening her up to new audiences, and generating 100 million streams on Spotify alone.

What’s more, this is the third time the song has enjoyed a social media resurgence, having previously resurfaced on the mothballed apps Musical.ly and Vine.

“All of a sudden the streams in France get really high and you’re like, ‘What’s going on?'” Styrke recalls.

“And then you discover it’s a big sound on some social media platform.

“Back in the Vine days, I’d play in places where I’d never been before and suddenly everybody would know that song.

“The power those platforms have is incredible – but I’m glad that songs that aren’t released this year can have a second life and live on and be relevant.”